What is Good Practice in Clinical Cancer Care?

Good practice in clinical cancer care is defined by service specifications and guidelines from international and national governmental and non-governmental organisations (4, 5, and 11). Its value is determined by the analysis of good quality data to indicate that there are distinct and causative relationships between the practice which is advocated and the good outcomes achieved for cancer patients and for general populations and citizens.

The European Cancer Organisation has set out the Essential Requirements for Quality Cancer Care (ERQCC) for a number of cancers (breast, prostate, oesophageal/gastric, lung and colorectal cancers, melanoma and sarcoma) and primary care; work is in progress to complete the ERQCC for pancreatic, ovarian cancer and glioma (36-43). The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) has a standard methodology for producing its comprehensive portfolio of topic- and disease-specific clinical guidelines, which are to be found on its website (44). The European Commission has supported Member State Joint Actions against cancer (EPAAC and CanCon which have reported and iPAAC in progress), which provide frameworks for action to improve cancer outcomes (5, 11, 12). Cancer societies promote good cancer practice individually and as part of collective European anti-cancer efforts (13, 25, 35, 44-57).

International and national specifications and guidelines emphasise:

- Patient-centred, specialized, and integrated multidisciplinary care, leading to the best possible survival and QoL for patients [The Code 1-4 and 7], including the delivery of the best available modalities of treatment (often combined), and the timely delivery of the best supportive care:

- Surgery [The Code 1] (25)

- Radiotherapy [The Code 1] (45)

- Chemotherapy [The Code 1] (44)

- Biological and immunological therapy [The Code 1 and 6] (44)

- Psychosocial care [The Code 5 and 7] (7, 55-56)

- Palliative care at all stages [The Code 8] (7, 57)

- The involvement of a wide range of professional groups in the planning and delivery of cancer care is a hallmark of good practice (25, 35, 44-57).

- Attention must be given to all age groups, including those with age-specific requirements including children (54), adolescents and young adults (58), and older cancer patients (33-35) [The Code 1].

- Good communication between patients and healthcare professionals about the patient’s diagnosis and treatment and the quality and outcomes of the care in a cancer service. Shared decision-making where it is the patient’s wish [The Code 2, 3 and 5] (7, 55, 59)

- Well organised care integrated across a region as a network to deliver best care, as near to a patient’s home as is safe and feasible [The Code 4] (5, 11)

- Research and innovation as a core part of the work of the cancer care team [The Code 6] (1-20, 53, 60)

- Survivorship planning, rehabilitation and support for reintegration into family, social and working lives [The Code 9 and 10] (2-5, 61-65)

- An active programme of oncology education [The Code 1-10] (66)

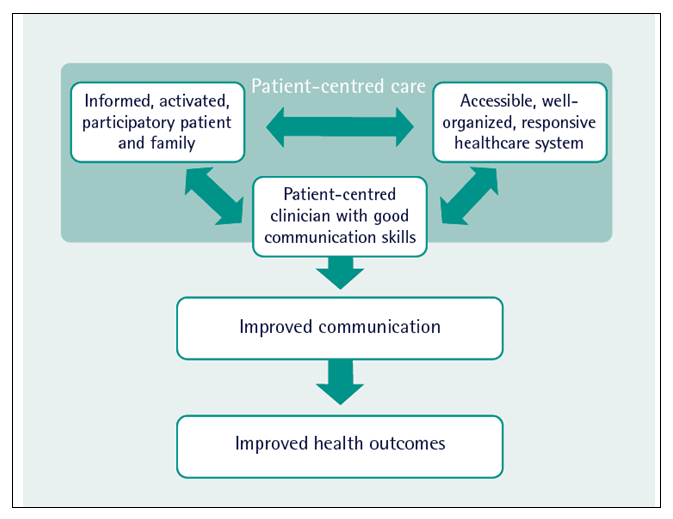

The ideas which underpin patient-centred care are current and topical but are not entirely new. In 1995, one of the earliest descriptions of a plan for cancer services noted “The development of cancer services should be patient-centred and should take account of patients, families and carers’ views and preferences as well as those professionals involved in cancer care. Individual’s perceptions of their needs may differ from those of the professional. Good communication between professionals and patients is especially important (67).” Abrahams and colleagues (68) brought this definition up-to-date and it is summarised in Figure 7.

Figure 7. A model for patient-centred care (adapted from Abrahams et al, 68)

Currently, European countries’ cancer care and cancer services are organised in different ways reflecting history, population, health system structure and resources. In most systems, there is room for improvement despite the existence of national cancer plans in most European countries.

Expertise is cancer care is often centralised into cancer centres which may be a part of a main general hospital or are separate institutions. A single agreed definition of a comprehensive cancer centre does not exist, but the Organisation of European Cancer Institutes (OECI), in its voluntary accreditation procedure, lays emphasis on a wide range of elements, including infrastructure for cancer care, human resources, clinical care activities, research activities, education and institutional structure (69). The OECI standards, which include academic and research activities and credentials, are an important part of Europe’s cancer care activities and frequently provide beacons of excellence which can be linked to other care facilities within different European countries and regions. The delivery of good clinical cancer practice in specialised Multidisciplinary Teams, often linked together through cancer networks is described under The Code 4 below.

The factors which determine good quality cancer practice and the resources they require, have been studied in detail. They include:

Workforce

The availability of adequate numbers of highly trained professional teams is essential to the delivery of excellent care and it is known that there is considerable variation across Europe in the provision of this key resource [see The Code 1] (2-11, 25, 35, 44-57, 70).

Estate and Equipment

Good quality cancer practice is critically dependent on the availability of the appropriate facilities and equipment, providing inpatient and outpatient diagnostic, treatment and follow-up facilities. For example, key equipment resources such as radiotherapy machinery are distributed unevenly across European countries and this disparity is associated with differences in patient outcomes [The Code 1] (71-72).

Facilities for patient support are important. Many hospitals will now provide patient support facilities which allow patients to access information and advice. This can create a “safe space” to which they can return and access support and advice from appropriately trained professionals in oncology, supportive care and palliative care disciplines. The good communications highlighted in The Code 2 can only take place in appropriately built and staffed facilities, where quiet discussions are possible and private rooms are available.

Service Volumes

There is a substantial medical literature on the relationship between the volume of patient care activity conducted by a healthcare team or institution and the outcome of that activity. In general, the evidence supports the view that in order to develop and sustain their expertise at the highest level, teams and institutions require a substantial volume of work, usually expressed in terms of patient numbers per year, to ensure that their expertise is sustained through constant delivery of practice. For example, it is now common practice across Europe for surgical teams to have a required minimum number of operations or other activities in any year in order to sustain their accreditation. This literature is complex and depends very much upon the nature of the activity being undertaken. Large and complex operations, for example, require considerable and sustained experience and this may often result in the need for centralisation of these activities in a limited number of hospitals or cancer centres. Planning complex care for patients with rare or advanced cancers may also require a highly specialised team and similar patterns of referral to a limited number of hospitals and this will be a feature of a well-coordinated national cancer plan (73-81).

While the delivery of cancer care to a required minimum number of patients inevitably creates a pressure to centralise care in a smaller number of institutions, this is not always required and flexible integration of care across regions is possible and can be effective. Many aspects of cancer care can be delivered close to a patient’s home and this can include aspects of diagnosis, follow-up and the delivery of some of the more relatively straightforward cancer treatments such as oral medication and some intravenous treatments [The Code 4] (73-81). This has been an increasingly employed mode of practice in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic although patients are still facing delays in diagnosis and treatment.

Information Systems

Measuring the performance and quality of cancer care services and programmes is essential to ensure that objectives are being met. It is necessary to have robust information technology systems to support improvements in cancer control in the network, with clear legal and administrative frameworks for the collection, sharing and reporting of data (5, 82).

Back to Medical Literature and Evidence for the European Code of Cancer Practice